When you start to doubt yourself, design from the inside out

Hard times force hard questions about the value of my work. The answers revealed the worth I was missing in myself.

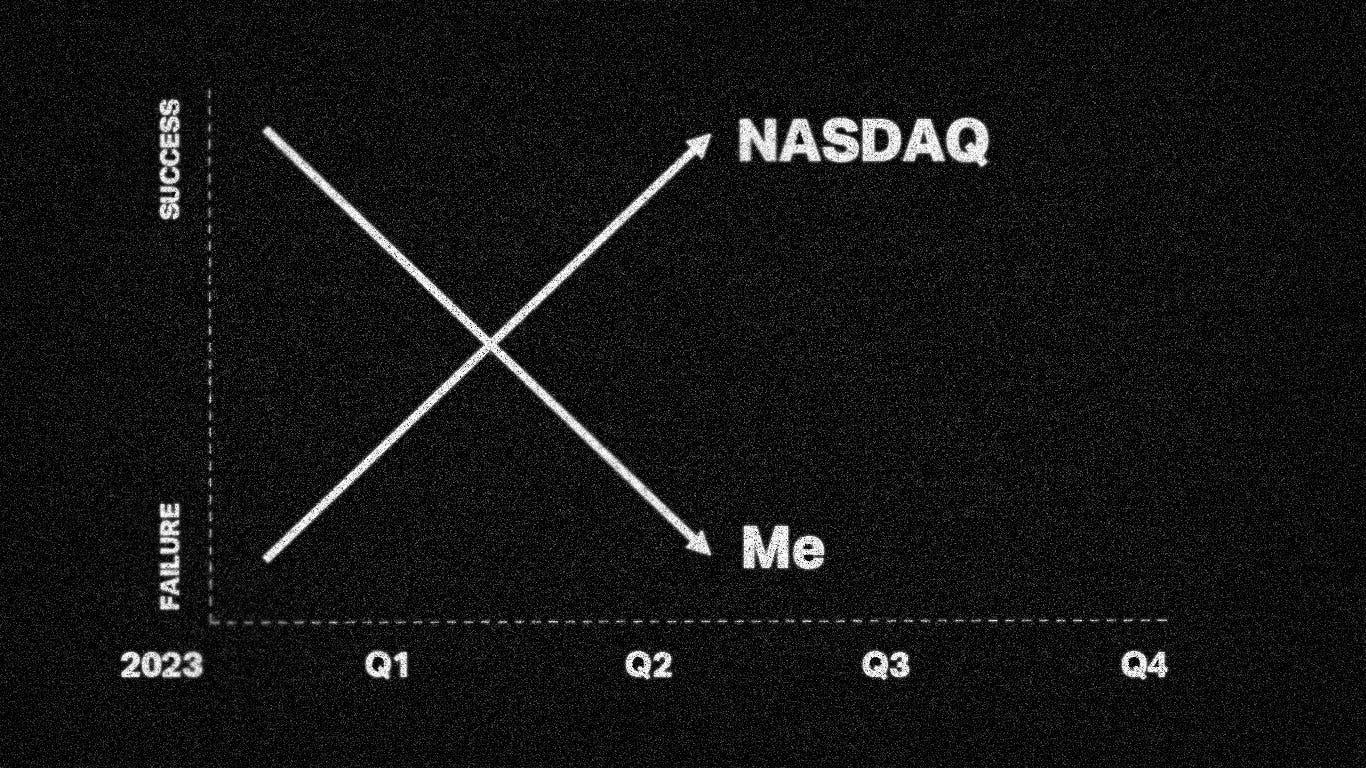

It was June 30th, 2023. The end of H1; the close of Q2, as my public-company employed colleagues like to say. I smiled as I read the headline again. I didn’t smile because I was happy, but because life has its own special kind of humor. Hidden in it is often a lesson. And if you allow yourself to laugh, you just might learn something.

In my own four decades on this earth, the start of this year, is, and remains, the exact opposite of the headline above. For the first time in my 25-year career as a Creative and Design Director, I am involuntarily unemployed, discouraged, and doubting more than just my vocational calling.

As the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations records historic profits, I have experienced losses at proportions usually reserved for a melodramatic opening chapter of a paperback self-help book you’d see in an airport bookstore, or a country western song. The details of which, I will reserve for the premium hourly rate of my therapist, and bury deep beneath my lustrous LinkedIn profile.

But instead of hiding the real things it has taught me, I am going to share them.

That headline did something to me. It cracked a dam holding back a lake of doubt and conflict. One I have been swimming in for my entire career. Recently, the waters have been rising. From the fissure flowed a series of questions. Questions I have needed to answer for a long time.

How can this year be so good for the market, yet so bad for my career?

Let me translate this into a more specific professional question:

What are the internal choices I have made, and the external factors at play, that have led to such stark and inversely correlated outcomes between the aggregated performance of business and my individual professional experience?

Now, translate it into the real and personal question I am really asking myself:

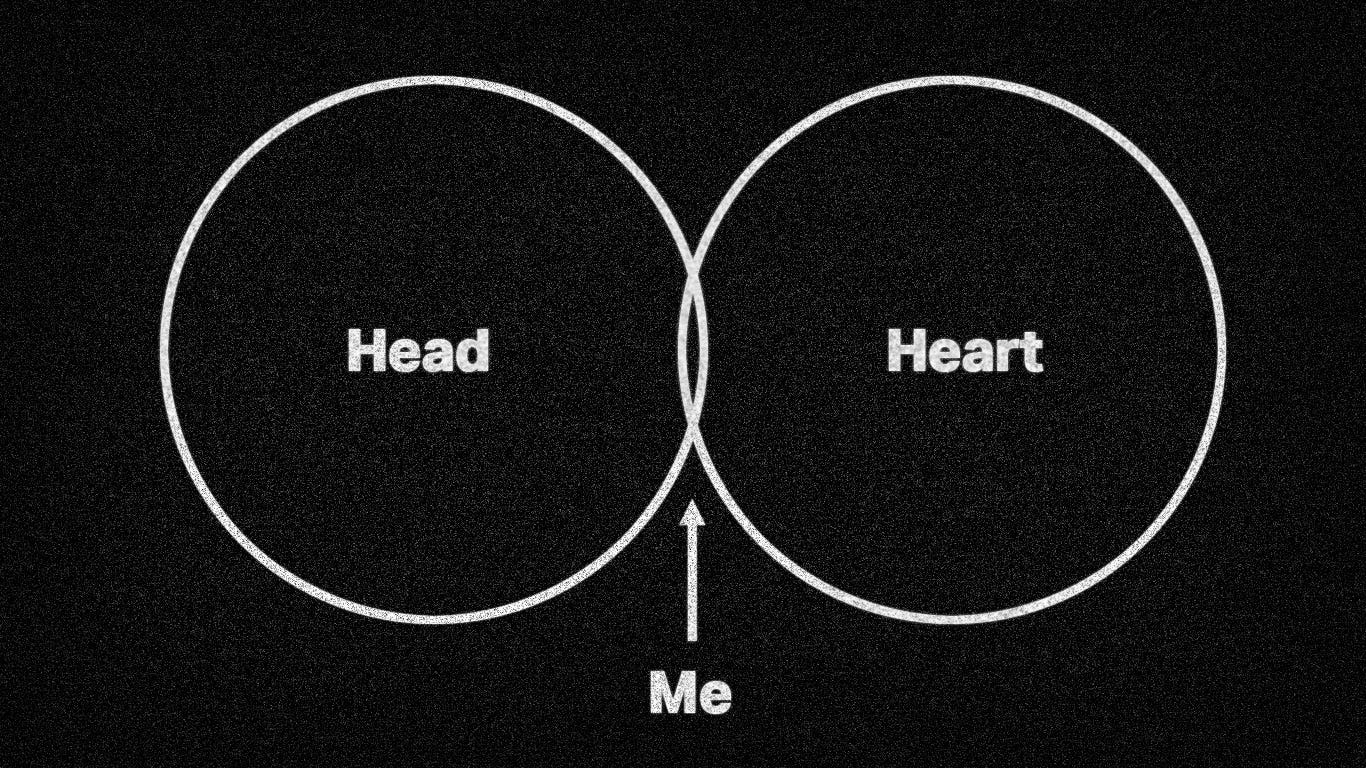

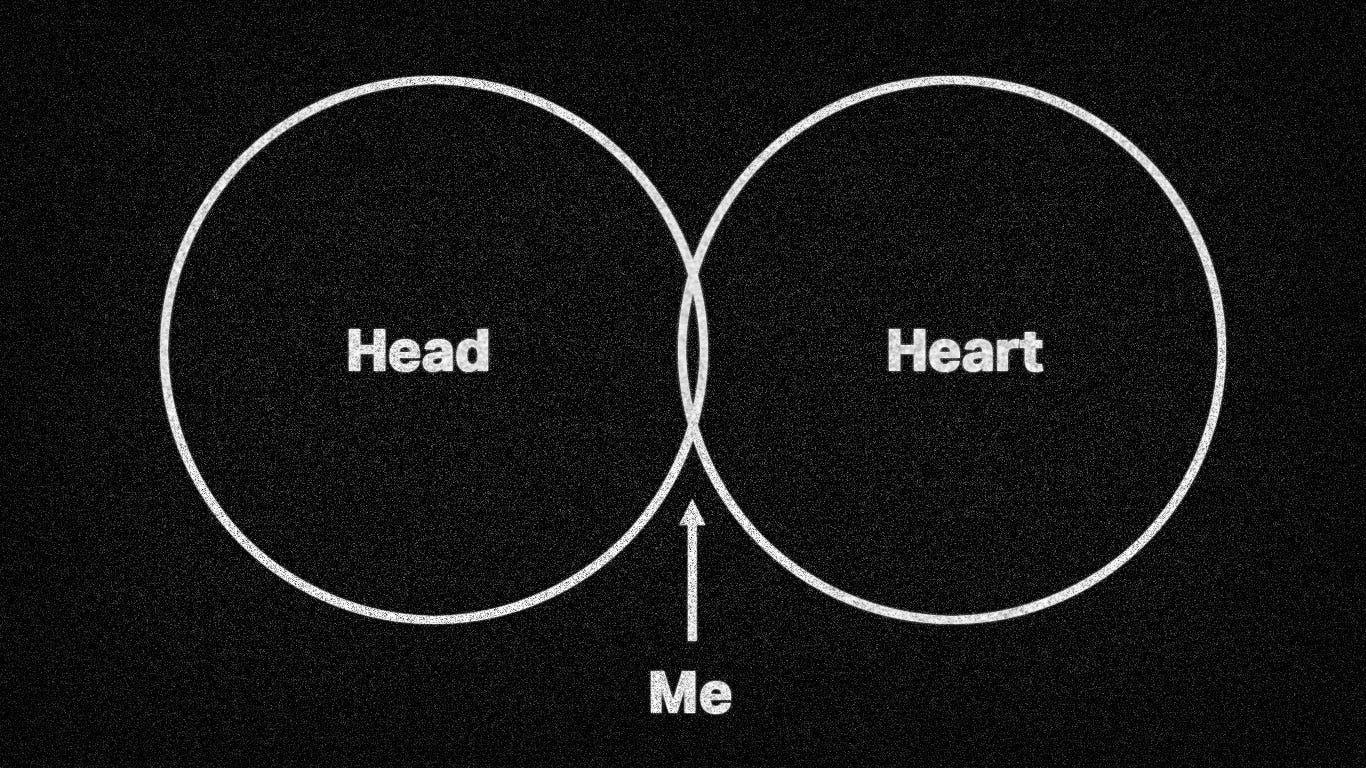

What is my worth as a designer?

But the real question I found at the bottom of that murky lake was the hardest to ask:

What is my value?

What you read next gets personal.

Yet, if doubt, insecurity, and a yearning for your own purpose are things we all share, then perhaps it is also universal.

These questions revealed the following beliefs I have had my entire life. They have hindered my happiness, my kindness towards others, and inevitably, my career. I am now facing them. How I am doing that is what you are reading now. It is time to tackle my own kind of Identity Design. I can’t hire this job out.

Facing these self-beliefs has helped me find my worth as a designer, but also as a person. Both will be better for it. My hope is that if you keep reading, maybe it can help you find something you might be looking for too.

My Belief #1: Design doesn’t matter.

The world can be plenty ugly, and a career in the creative economy rarely will get you to the corner office. Over the winding course of my own journey through this discipline, I have had my moments of doubt. Not only about my career choice, but about my core belief in design. I was taught early to“Never trust a book by its cover.” and that “Beauty is only skin deep.” I learned that appearances are superficial. I had a didactic childhood. I was raised by teachers in the rural Midwestern United States, where Puritan and Protestant ethics still haunt us and blow like ghosts through the cornfields in late July. But I was also raised to follow my passions, despite not knowing anybody else as a kid who liked to paint and draw. These lessons informed who I am. Perhaps the real lesson is: paradox is part of life, and life is complicated.

You might already see the conflict. There’s been a Civil War in my head lasting decades. What if I am the one designing the book cover, what if the skin in question is a user interface? Despite being obsessed with the details of appearance and form (it once took me 3 days to find the right powder coated lag screws when building a chicken coop. The wafer head and black oxide coating needed to be just right), I harbor a deep strain of guilt and fear of being shallow and materialistic. When your own career can feel like a guilty pleasure, you end up in a complex and relationship with your work, and with yourself.

I have been asked hundreds of times in the last several decades if I could “make it pretty.” And I usually did. And I like doing it. Usually. Since my first professional job in high school (a logo for the concession stand at public city pool in the nearest town), I have been asked to make things look better. And that is a noble pursuit. I enjoy doing it. I got good at it. People care how things look and appearance is powerful and visceral mode of communication. Graphic Design and the visual arts are a core love of mine and my first passion. (The concession stand manager never paid me. When I told my school principal, she intervened on my behalf. I got my $100. I don’t remember what I spent it on. What lasted far longer: a sense of embarrassment that my work lacked real worth.)

When I believe that design doesn’t matter, I am forgetting what design really is. Naturally, over a lifetime of practice, my understanding of the discipline of design became both broader, and deeper. I started with the skin, and went to the bones.

Design can be — and is — more than a measure of how things look. Steve Jobs said “…design is how things work.” and people in my line work love to quote that. I say it a little differently: Design is a quality of how things are. Successful design achieves both rational and irrational criteria. It stirs the emotion and the intellect. Two things can be true at the same time. Design is about how the thing feels. And feeling is part of being alive. It is what makes us alive.

Before I continue: if you prefer to replace design with the word ‘creativity’ — do it. My position is: Creativity is problem solving in ways that are clever and beautiful. Design. Creativity. It is the act of Making. A tomato or a tomatoe.

You’ve heard enough about my own past. Now for the present: for a business to work, especially in 2023, it needs to be designed well. It needs to be clever. It needs to be efficient. It needs to be lean. And it always helps to be beautiful. Good design is as little design as possible, don’t forget. That means every element needs to contribute to the intended outcome. Those parts that don’t contribute are removed. Those that don’t contribute enough are reduced in size proportionate to their value. You’d do the same for any composition, signage, or state of a product you design.

The previous tough-love paragraph is only part true. When individual designers, whole teams, entire business units, or whole businesses are laid off, RIF’ed, terminated or closed, it is because they either cost more money than they make, or, because removing them is a faster to post revenue via cost reduction. The latter has tempted many a C-Suite this year. See above:the opening sentence to this essay.

It takes hard work to make money. It takes hard decisions to save money.

If design is not achieving the stated goals, or not doing so fast enough, or efficiently enough, it doesn’t mean it is not good design. It means it is in service of the wrong outcomes at the present time. And at the present time, the interest rate is no longer zero, and the cost of money is rising. Design, like all professions need to pay for themselves. Outside capital isn’t anymore.

Design does matter. It can play a key role in the success of a business. Gooddesign doesn’t fail. Lack of speed to value, or patience, or the ability to show it’s value in service of Net Income Ratio is what fails. And yes, the federal interest rate plays a factor too. Like good design, the fed rate affects people’s emotions and their intellect. And every decision a CEO makes includes a little bit of both.

Design solves problems. And in this market, business problems are bigger than user problems. Design accordingly. And never be afraid or ashamed to make beautiful things.

My Belief #2: I care about the wrong things.

I have always struggled with insecurity. Mine is an inferiority complex. It comes from an inherited consciousness and a class awareness I have harbored. Remember, I am a Midwestern, rural, public-school educated kid. I hold two liberal arts degree. I was taught to work hard, look people in the eye, and stick around and help fold up the chairs after the dance is over. This meant my high school and college years where spent working as a janitor, in hay fields, and as a landscaper. My youth was not networking with prep-school families, interning at Goldman Sachs, nor learning the ins and outs of market analysis and global financial instruments. Early in my career, I learned how to make books, signs, websites, mobile apps, and entire brands and that people could use and enjoy, not P&Ls for capital investments to buy and sell.

I have always been self-conscious about this. I have always felt I lack the sophistication, the connections, and the good breeding to succeed professionally in late capitalism. I have always had embarrassment for caring about the wrong things, and wearing those passions on my sleeve. I spent a lot of time resenting my strengths and desiring my weaknesses. I began to think and talk badly about myself. Far worse, I would talk poorly about others I cared about who shared my interests and abilities — as if those who want and are able to bring more beauty, meaning, and elegance into the world should be made to feel as regretful and as foolish as I did.

The more I fixated on this, the worse my happiness and my relationships got. Thinking that creativity doesn’t matter is not only wrong, but selfish. Thinking that people who care about creativity are wrong is worse. I have worked, thought about, debated, and in many ways lived my life through creativity and design. It is part of my identity. Too much, in fact. Over time, the negative self-talk and embarrassment became a monologue. It led to a far bigger mistake: I began thinking that I didn’t matter. I focused on others who achieved more outward success. I watched company valuations grow, while (and because) design teams were laid off and creative investments got shut down. I saw all of this as proof that I lacked the intellect and skills to succeed.

I lost my passion and then I lost my sense of worth, and then my kindness.

Marcus Aurelius was a Roman emperor. By every account, one of the good ones. He said, “Tranquility comes when you stop caring what they say. Or think, or do. Only what you do.” Businesses can abandon design, and trade it for short-term profits. That is what is in their nature. I don’t need to have an opinion about what they do. Individuals can pursue, and attain wealth by ignoring the things that matter to me. That is their nature, they are succeeding by their own terms; not mine. I should let them be happy, and not let it determine mine. Most importantly, I should stop listening to the voice that has developed in my own head, telling me I am foolish for pursing what animates me and what makes me happy when I am doing it.

My Belief #3: I am not [smart, savvy, successful] enough.

A consequence of someone with an inferiority complex is that they overcompensate. A few years ago, as went barreling into middle age, and my family expenses began to eclipse my income, I asked my manager how I could advance my career. I worked at IBM, and in corporate speak, this meant I was asking my boss how I could increase my salary. IBM has a long and storied history in Design. IBM however, is a sales company. I learned that in my current role, as a Creative and Design Director (a sub-median Band 9 for those in the corporate world) had reached it’s ceiling. But, I was informed, there was a career path as Partner. So I enrolled in the IBM Partner Apprentice program.

I became a Salesman.

I overcompensated.

I spent 9 months among a competitive cohort from across the United States. I never met any of them in person, but I suspect none had ever bailed hay. I was out of my element, but at least it was on my own terms. I learned a lot. I took classes in the theater of a sales pitch, deal structuring and risk assessment, and how to negotiate sales credits and secure them in Salesforce. I also learned that I am not a money guy. I am a design guy.

Money is just not my medium. I no longer work at IBM.

The moral of this story: Do I care about the wrong things? For many, I do. For those, the value of creativity and design is an intangible asset whose relevance and value does not have a place on a balance sheet — or anywhere, really.

But that doesn’t mean I need to be ashamed. I care about design because I believe it is what makes our lives more satisfying, beautiful, and useful for ourselves and others.

Our values are revealed in our actions. I build things. I make things. I want to see better form and function and beauty around me and I am compelled to try and make that happen.

Our actions are determined by our passions. I build things whether I am paid to or not. I want my daughters to have a thoughtful and functional shoe cabinet and bench to put them on in the garage to cultivate good habits and a clean house as much or more than I want a Fortune 500 company’s e-commerce site to have a seamless checkout to reduce cart abandonment.

Our passions show us who we are. We need to focus on the merits of what we love more than their consequences. The world needs beauty as much as it needs money. From my observations, once the latter is acquired, it is spent on the former anyways. No one should be ashamed of what matters to them, and never be embarrassed by working hard to achieve it. It is ok to make both.

My Belief #4: I don’t matter.

This is the real personal part. After a quarter century of working as a professional creative and designer, it has become a central aspect to my identity. It is both how I make money, and often how I spend it. The act of making scratches an itch in me I haven’t found anywhere else. It gets me into a flow state. It allows me to transform my energy into matter — to convert a compulsion in me into some real, something to see, hold, and use. Maybe most importantly: it is how I express my appreciation and affection for others. It is my love language.

If I make you something, I am trying to show you I love you. In my professional work, it is of the Agape variety where make things for people (aka “users”) I will never know. If I give you an 80-year old Axe I have found and restored, I am telling you I love you, in the Philia sense. The way I design and build a chicken coop, renovate and create my home, make the furniture in it, and create the toys and games I play with my kids, that is Storge love.Building at treehouse in the woods for myself and my family? — Both Philautia and Pragma love.

When the thing that propels a career, animates hobbies, and becomes a mode of communication are the all same, there are drawbacks. For one, my sense of worth and accomplishment is less diverse. When the market, the end users, my friends, or my family don’t appreciate or acknowledge when I show them I love them, it can hurt. I’ll admit it. It is easy to feel like I don’t matter. But then, I have always been sensitive. I am working on that. I am also getting a lot of opportunities to practice.

Your Work Won’t Love You Back. Neither will the Stock Market. Your employer won’t either. Nor will you boss, your customers, or end users. Sometimes even those you love most won’t be able to show you it in return. Don’t go looking for it on Dribble, Behance or Instagram either. If you are at all like me, someone who “Is a designer”, do yourself a favor. Be proud of what you do, and who you are. You have value. You make the world a little better place to be in. Also know it won’t always love you back.

You are not only “a designer” or “a creative”. Don’t forget you are also many other things. A father, or a mother. Maybe a wife or a husband, a son, a daughter, and a friend. It is in those roles you will find much more of the love you are looking for.

2023 has been hard. It has also been a teacher. Sometimes, the pursuit of more reasoned answers about the outside world require acceptance of what is inside us. We all come to our own self-awareness, our own value, and learn to own our identity in our own ways. This is mine.

The most important identity design project is your own. It is hard. It might take a lifetime. We all have our own paths to walk. Create, design, and make the most of it.

Comments are closed.